New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

New Orleans: From “BlightState” to Preventing Fire Fatalities.

Project Type:

Economic Development, Education, Energy, High-Performing Government, Housing, Public Safety, Youth Development

At a Glance

Created a data-driven performance management program and a website that aggregates data about important housing information to address blighted homes post-Hurricane Katrina, resulting in more than 15,000 fewer blighted addresses by 2018.

Worked with What Works Cities partner the Behavioral Insights Team to devise a “nudge” letter to owners about housing violations, resulting in a 10 percent drop in cases moving to the hearing stage, saving staff time and city funds.

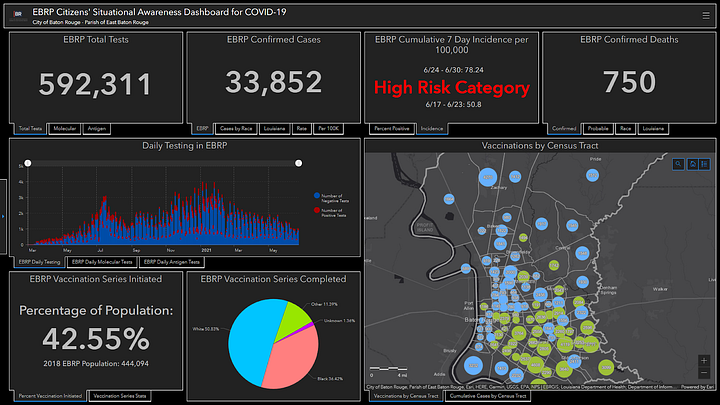

Developed a predictive model that identified which parts of the city were most at risk for fires and fire fatalities using that information to target its campaign to distribute smoke alarms to vulnerable households.

Targeted anti-gang violence via prevention efforts and rehabilitation, which led to an 18 percent decrease in the number of murders as of 2016.

New Orleans’ Creation of New Orleans

One Thursday morning, some ten city officials seated in a u-formation of tables faced an audience of some two dozen local residents in a room at New Orleans City Hall. The city staff and residents all knew each other by first name, and they bantered a bit back and forth, which was no surprise as many have been regulars at this monthly meeting for years, regularly returning to follow progress and to fight for the removal of blighted properties that have proven more difficult to address in their neighborhoods.

BlightStat, a data-driven performance management program, has been in place since 2010. When Mayor Mitch Landrieu took office in May 2010, New Orleans faced what has been described as one of the worst blight problems in the U.S., “with no strategy to address it,” the City notes. A large part of the problem was the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the city in 2005. Five years later, faced with thousands of homes that could not be saved, Mayor Landrieu instituted BlightStat to ensure that the City’s efforts to get rid of the blighted homes would proceed efficiently and effectively.

BlightStat set priorities for the inspectors and researchers who identify rundown properties and determine whether to levy fines, order a demolition, force a sale, or take some other action. Under the BlightStat framework, the City considers issues such as the condition of the roof and foundation, the owner’s history of tax payment, and the market for real estate in that neighborhood, trying to predict the cases that will have the best outcomes so that the Department of Code Enforcement can decide how to best to deploy its resources.

The City also created BlightStatus, a website that aggregates data about inspections, code compliance, hearings, judgments, and foreclosures, providing users with a simple search box that unlocks all the information available for any address in the city. It opened up a new, easy-to-use link between the city and community, keeping everyone on the same page and giving residents the chance to make their voices heard. The tool also helped city employees keep up-to-date with changes to properties and stay accountable for promised changes.

By 2018, New Orleans had more than 15,000 fewer blighted addresses, accomplished through a mix of demolition, sale, and owner repairs, aiding vastly in New Orleans’ recovery.

New Orleans also worked with What Works Cities partner the Behavioral Insights Team to devise a “nudge” letter to owners about housing violations, resulting in a 10 percent drop in cases moving to the hearing stage, saving staff time and city funds.

New Orleans’ use of data undergirds many of its major programs. “We use data to plan. We use data to create an iterative process that informs implementation. Data is baked into our culture; it’s a part of our subconscious,” says Oliver Wise, former Director of the Office of Performance and Accountability (OPA), who was succeeded by Melissa Schigoda.

OPA runs the City’s data analytics initiatives. Along with BlightStat, they include ResultsNOLA, which evaluates the performance of city departments, and NOLAlytics, which helps those departments conduct their own data analytics projects to support their missions.

In one project, OPA developed a predictive model that identified which parts of the city were most at risk for fires and fire fatalities. The City used that information to target its campaign to distribute smoke alarms to vulnerable households. Using analytics, it identified twice as many households in need of smoke alarms than it had when the City chose households at random. Less than a year later, there was a fire in an apartment building in one of the neighborhoods that the City had identified, and eleven people escaped — all because of a very cheap, but strategically installed, smoke alarm.

To address its high murder rate, the City instituted its NOLA for Life initiative in 2012, targeting anti-gang violence via prevention efforts and rehabilitation, which led to an 18 percent decrease in the number of murders, as of 2016.

Mayor Landrieu, who left office in May 2018 after serving two terms, says he has always been data-driven, realizing that if you can’t measure something, you can’t assess outcomes. “Data shouldn’t make you look good — it’s intended to tell you the truth,” he says. “The results can speak for themselves.”

Landrieu says he told staff from the start that he “wanted to count everything” and to fold that sensibility into the budgeting process to run a “leaner, more efficient government.”

Landrieu says a “culture of counting” will have a real impact on the ground and make a difference in people’s lives. He created a Neighborhood Engagement Office to ensure managers are more connected to residents and see to it that “everybody’s data can matter.

As he looks back at his administration, Landrieu says he’s most proud of the team he assembled for their focus on getting things done in a data-driven fashion, and the processes they put into place to encourage innovation. “These processes were designed to last,” he says, “not to be a flash in the pan.”

“If you measure and it’s real, you gain the confidence of the public.”