Portland, Oregon, USA

Keep Portland Data-Driven.

Project Type:

Communications, Health and Wellness, High-Performing Government, Public Safety

At a Glance

Continually using data to scale up programs that work and moving away from programs that don’t – making the most of limited resources and improving the delivery of services to residents.

Used randomized control trials to test the best way to encourage social distancing during the early days of COVID-19.

To reimagine public safety services, Portland Street Response used geographical data to determine whether a situation warrants a response from police or mental and/or physical support services teams – which helped determine which areas were in most need of social service resources.

Celebrating Oregon

Portland, Oregon has long been celebrated for thriving cultural scenes that produce outstanding artisanal foods, craft beer, and music. Talk to a good governance wonk about the City, though, and something else might come up: randomized control trials. One of the most rigorous tools for evaluating whether something actually works as intended, the trials were all over the news in recent years as pharmaceutical companies developed COVID-19 vaccines. But governments are increasingly using this valuable evidence-building innovation tool as well. Portland has been a trend-setter.

Over the past few years, the City has emerged as a public-sector leader in data-driven evaluations, leveraging randomized control trials to support social distancing public health messaging, police recruitment, and disaster preparedness efforts. By learning what works, city leaders have been able to scale up programs and messages with confidence, making the most of limited resources and improving the delivery of services to residents. And if a trial reveals an intervention doesn’t have impact? That’s valuable too, allowing staff to pivot away from less effective ends to different approaches, and avoid wasting time and city resources.

Building the City’s Evaluation Muscle

“The reality is that sometimes what we think will work doesn’t work,” says Lindsey Maser, who works in the City’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. “Rigorous, data-driven evaluation methods allow us to understand what works, for whom, and by how much.”

Maser coordinates citywide behavioral science and evaluation efforts, and has spent the last half-decade working with staff across the City to strengthen Portland’s evaluation muscles with support from The Behavioral Insights Team (BIT), an expert partner of What Works Cities.

As of early 2021, staff across the City have run 19 different randomized control trials. The basic approach of these trials is this: create statistically similar test groups, including one that experiences the intervention and one that does not. Then compare the results of the groups to see if the behavior of intervention group participants changed in desired ways.

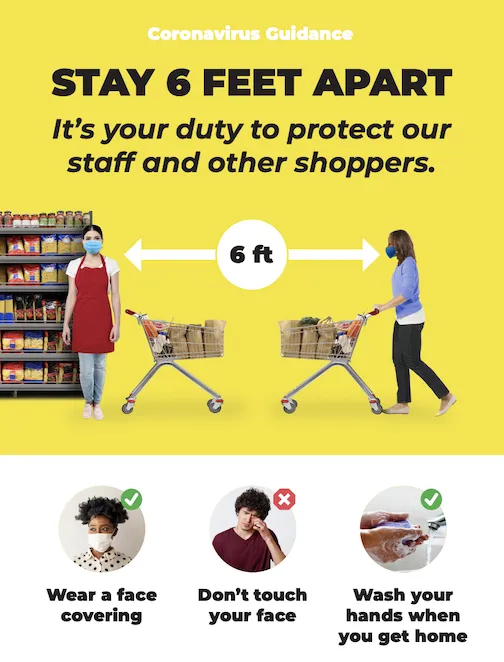

One example: Testing the best way to encourage social distancing during the early days of COVID-19. In April 2020, when it became clear the City needed to deliver effective public health messages to residents, Maser and staff at the Bureau of Emergency Management jumped at the opportunity to work with BIT. They got to work designing and testing posters to encourage grocery shoppers to stay six-feet away from store staff and customers to prevent the spread of the virus.

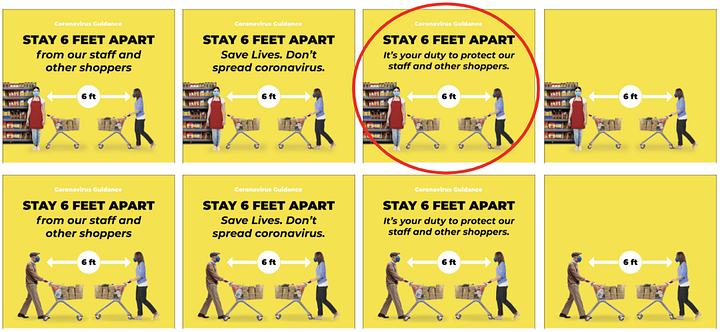

Eight variations of a poster were tested via an online randomized controlled trial. Among other things, the results showed that using a message of duty to protect others and showing an image of grocery store staff increased the number of people who understood and remembered the need to stay six feet apart.

“It was incredibly helpful to be able to test a bunch of ideas so quickly and move forward with confidence,” Maser says. The City distributed copies of the poster to grocery stores and heard grateful feedback from store owners who were worried about their staff’s safety. BIT helped design the poster based on COVID-related messaging trials done elsewhere, and then shared Portland’s findings with governments across the U.S. and abroad.

“Portland takes every opportunity to pursue meaningful evaluations. Its staff knows how to scope an opportunity, and they have the skills to follow through due to their range of evaluation experiences across departments.”

The City’s commitment to evaluations has inspired other cities, and they’ve been quick to join BIT-led multi-city trial cohorts, including efforts to decrease 911 dispatcher burnout and increase voter turnouts.

A New Evaluation Normal

Maser is proud of the City’s evaluation efforts and how they’ve generated data to show the best path forward. But she also notes that randomized control trials can be time-consuming and require new ways of working. Building a strong muscle for evaluation work often requires cross-departmental collaboration and buy-in. That can be challenging, especially in the last large U.S. city operating under a commission form of government, in which the executive function is split amongst members of council. This structure has a tendency to breed silos, but Portland has risen to meet this challenge, showing other cities that there’s always a way.

And then there’s the reality that not all trials offer decisive results for the City.

“We’ve tested things we thought would have a positive impact, and then saw no effect,” Maser said. “While it can be disappointing, we always learn something that helps us keep improving.” In some trials, teams have realized they had to do something bigger to have an impact.

“The scale of the intervention needs to meet the scale of the problem. Having clear data gives staff evidence to advocate for more resources.”

Portland’s culture of data-driven evaluation has spread across the City. After working with BIT on multiple randomized control trials, city staff have started running their own. A staff member with the Environmental Services department tested different approaches to increase signups for a water bill discount program, and the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management ran a trial aiming to increase city employee preparedness for earthquakes. All this work is made visible to city staff via an internal e-newsletter and the public via the City’s website.

One high-visibility data-driven pilot launched in early 2021 is Portland Street Response, part of city efforts to reimagine public safety services. Designed in partnership with Portland State University, the program aims to assist people experiencing homelessness or low-acuity behavioral health issues. If 911 dispatchers determine a situation does not warrant a response from police, firefighters, or an ambulance service, a street response team featuring a therapist, paramedic, and two community health workers is sent instead.

The pilot’s geographical focus is the product of an analysis showing that 60 percent of resident complaints received via 911 calls occurred in the greater Lents neighborhood. It’s a highly diverse half-square-mile area — 150 languages are spoken by Lents residents — that lacks social service resources. The pilot kicked off in February 2021 and expanded its boundaries in April. With additional street response teams added as time goes on, the City expects to be handling 30,000 service calls annually by 2022, with the twin goals of addressing the root causes of homelessness and reducing demand for police and fire department services. The City tracked data to support its evaluation of the pilot’s impact after six months and one year.

For Mayor Ted Wheeler, a data-driven mindset has become the norm in the City and the benefits are clear.

“I’m seeing and hearing more and more from staff who are embracing the benefit of evaluations. I don’t know of a single project in the City that does not use some kind of reliable statistic, survey, or data. Ultimately, that leads to more effective city communications, policies, and programs for residents.”